My relationship with birdsong is complicated. The music, the signal of rising light and warmth and nesting and babies of all sorts returning is intoxicating.

But it’s forever stamped in my mind with the explosion of cancer cells in Eric’s body, the cancer that killed him. He first started to seem sick in early spring, just as there was enough light to get out for a run before we both had to leave for work in the morning. Stepping out on the porch every day I heard more and more birdsong.

Then one morning as we headed up the small hill past the cemetery to the dirt road that turns into a woods road that turns into nothing, Eric touched his chest and said, “I think I pulled a muscle swimming the other day.”

I thought who pulls a muscle in their chest swimming but buried the thought. We both became adept at denial over the next month, as he got sicker and more consumed with pain and we kept acting like this was an inexplicably recalcitrant bad back.

It was a body full of cancer and by early May he was dead.

Everyone who knows me knows this story. How does it become more than just another story of someone losing someone they love? Especially now, when there’s a whole new category of how to lose a loved one? Maybe recognizing cycles and honoring them is a story we all need.

Yesterday morning I had a committee meeting of the land trust board I’m on and I did the Zoom call on my porch. Other people on the call could hear the birds in my yard and there were texts about the birds, asking what they were. I know I have robins, sparrows, chickadees, mourning doves, bluebirds, mockingbirds and bob-o-links in the pastures across the street.

But when I was asked what the song was punctuating the call, I didn’t know. I pay attention to the birds in my yard, but I’m not sure I want to be able to name the ones that mark the descent into illness for Eric.

I feel like a write a yahrzeit post every year on the anniversary of Eric’s death. But I know I don’t because I checked, and it’s now over a week past the day he died and I’m just getting this post up now. Maybe I was waiting to deal with the birdsong.

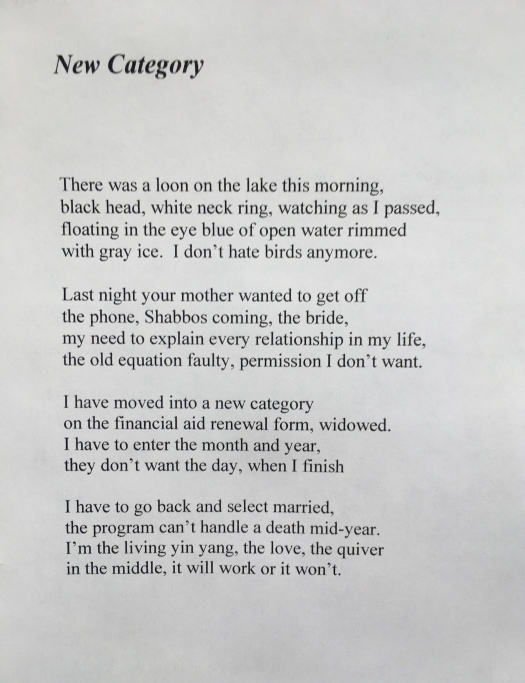

This is the first poem in my book about losing Eric, The Truth About Death. I’ve posted this poem before and I’ve certainly talked about losing Eric before. But as I said, maybe that’s the point, to remember that life has cycles and cycles and learning to turn with them can leave us in a better place. Like listening to and appreciating birdsong.

Birdsong

Now the song varies, mocking chains of notes,

the catbird flying from maple branch to fence post.

All spring I noticed the rise in birdsong

as we went out each morning, stronger chatter,

the brakes off, cells dividing and dooming themselves.

I sit in your chair, I wear your clothes, your ring.

I talk to your photographs. I watch the sky,

watch birds in the yard and realize how many flocks

I’d missed. For weeks I washed you, watched you,

lay next to you, all we could do was touch hands,

all you could do was whisper, your eyes black

morphine disks. Yet you turned back for me.