More happiness? Saturday I was walking with my sisters Meg and Chris and my brother-in-law John when we crossed a bridge over the Assabet River. Meg stopped and pointed to a bird among the branches of a small tree on the river bank. “I think that’s a blue bird,” she said and Chris and John and I all stopped next to Meg and leaned over the railing to look at the bird. “It looks brown,” Chris said and just as I was about to agree, I saw a glimpse of blue. The bird opened its wings and flew to a bush a bit upriver. Blue wings. “It is a bluebird,” Chris said. “Good luck,” said Meg. John said he hadn’t seen a blue bird in years.

I saw a flock of blue birds one morning last fall, and began writing 300 to 400 words each day for the next two weeks leading up to the winter solstice. Seeing a patch of blue birds cross my path running that morning made me decide to enact an idea I’d read about in The Sun. A small press had invited 30 writers to write 300-400 words each day during November, 2010. Chapbookpublisher.com then produced hand-bound books, one for each day by each author. That’s 900 books.

The decision stuck. I loved having a project that got me to my computer every day and that focused me beyond the light diminishing each day as we progressed to the darkest. And I was fascinated by the hand crafted books. Almost any type of paper crafting is satisfying to me, and nothing more so than making a book. The absorption of a creative project, whether writing or printing and folding and binding paper to make a book, is a circle of positive reinforcement. Letting the flow of creation take over, making something appear that wasn’t there before, that only existed in my head, makes my head feel lighter.

Looking for a new way in to that creative circle earlier this fall, I decided to make books of the haikus my family all wrote as part of our annual Labor Day weekend gathering this year. Meg had emailed and asked everyone (four generations) to write at least one haiku about summer (many people wrote more, including my father who wrote 14). As encouragement to get everyone writing, I offered to make a book for anyone who contributed a haiku, a collection of all the haikus that were shared. After the weekend was over, a number of family members still hadn’t contributed a haiku. As a further inducement, I asked everyone to make a cover for a book, and if you contributed a cover, you would get a book, even if you didn’t write a haiku. In the end, of course, I decided I’d make a book for every household in the family regardless of whether they wrote a haiku or made a cover. That’s 16 books.

Making the books has been a wonderfully absorbing project; it took me weeks of fiddling with the word document to get the poems set up to print on back-to-back pages correctly. I spent a conference call I was on last week standing at the kitchen counter as I cut the 13 pages for each of 16 books, neatly slicing the paper cutter’s razor roller up and down, making printed paper into pages.

But Saturday was the most fun. Meg and John met me at Chris’s house, and we spent part of the afternoon folding and glueing the pages of the books, then putting each set of pages into a cover. Not everyone in the family made a cover, but we had enough. Again, my father’s production outdid everyone. He made seven covers.

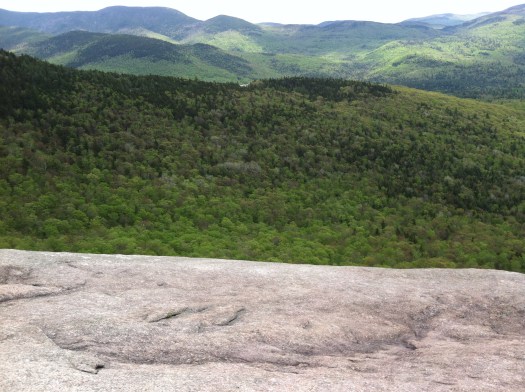

We’d gone on our walk before we started working on the books. The blue bird indeed seemed like a good sign, since we’d just been talking about the ever cycling reality of worry and difficulty and the utter messiness of life, and how much better we all felt being outdoors and walking. Some of the afternoon’s sun was still settled in our shoulders when we sat down to fold and glue. We quickly figured out faster ways to do every step of the book assembling process than what we first tried. We made mistakes and laughed, then fixed them. We were absorbed and focused. Meg and Chris and I have been doing this for 56 years, the first people I sat with at a table, working in the flow. How sweet.