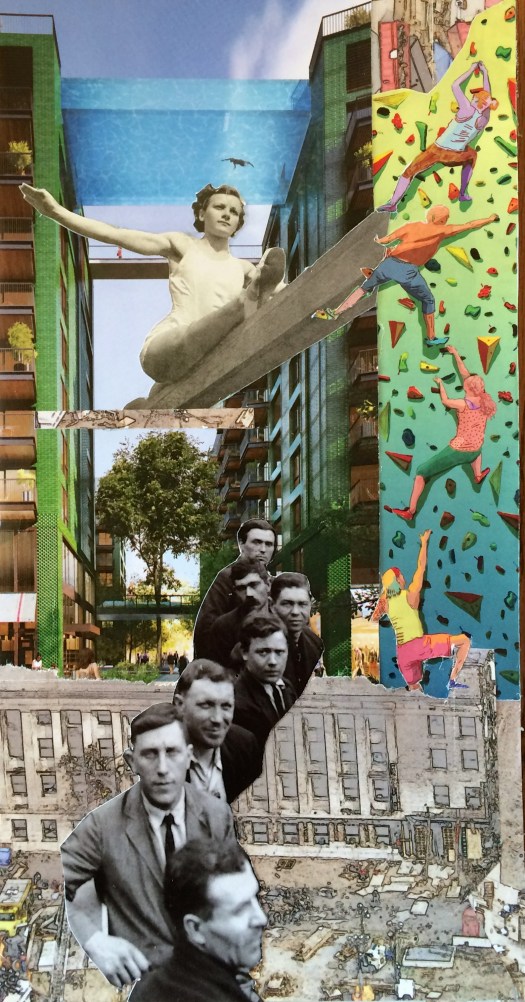

A friend once said “your poems are like photographs.” What I see goes in to words, translated through what I think, how I sort language to get the image I want on paper. Now I’m trying it without words. And loving it.

Journals

A not uncommon conversation for me over the years: What are you going to do with your journals when you die, or before you die? What instructions will you leave for whether or not they can be read, by whom, when, what can be shared? Or will you destroy them all at some point?

A poet friend records current events and notable weather in her journals, because she plans to leave them to be read and she figures that’s what people will want to know about — what was happening in the world, not in her head.

Which is what my journals are full of. There’s some recounting of events, but much of it is I’m anxious, I’m worried, I’m upset. . . blah, blah, blah. Another poet friend admits the same. “My journals are blah, blah, blah over and over.” Not that the blah isn’t important, it is to us, that’s why we’re writing it. But it probably would be boring to most other people, and would paint a false picture, anyway.

When my mood is mostly even and good I don’t journal much, I do it when I’m confused, when something is upsetting me and I need to figure it out. I write in my journal when I’m anxious because the act of getting worrisome thoughts on paper loosens their uncomfortable grip a bit. I’m honest in my journals about all the ways I’m quirky and irritable and over think the shit out of way too much.

So do I want anyone to read all of that? Would anyone want to? I’m talking serious numbers of journals — 82, including my blue plastic bound Ponytail Dear Diary with a brass lock (key long gone) from grade school.

Jon brought me three of Chris’s journals last week. He wondered if I wanted to read them. He doesn’t want to right now, though he wants to keep the journals. Do I want to read them? Should I? I’ve peeked in to them and so far haven’t read anything that I didn’t hear Chris talk about or haven’t read in her essays. Chris didn’t hide her feelings and worries and struggles. I loved that about her, her honesty about all of life, the joy and the hard road of living with metastatic cancer.

Chris took journaling classes in her last years, and in one she made a cover for the journal she was using. It’s beautiful. Right now it’s at the top of the journal stack on the side of my desk. I love looking at it. I don’t know if I’ll read it.

The Question

The Question

Hands raised palms out.

Hands clutched around a cupboard key.

Hands raised in anger, trembling.

Hands holding hands.

Hands raised in triumph at the end of a race.

Hands stirring a pot of stew.

Hands raised in surrender after a long argument.

Hands washed in a kitchen sink.

Hands raised in greeting to a stranger on the porch.

Hands resting on a crocheted afghan.

Hands raised to throw a whiffle ball to a child.

Hands balled to fists behind a back.

Hands raised to shoot the last bullet from the last gun.

Hands folding a tea towel.

Hands raised to catch a tossed packet of biscuits.

Hands open, up, fingers wide.

Hands raised in answer.

The Power of Ten

What is it about the years divisible by ten? All the milestone birthdays are in increments of ten — people especially note turning 30 or 40, 50 or 60. Money rolls out in increments of ten. We celebrate anniversaries of major events in tens — marriages, assassinations, great scientific achievements, disasters. Pretty much everything would be counted in tens if we used the metric system like the rest of the world. Ten means starting again, because that second digit comes in, the need to go back to the first finger to continue keeping track.

I’m thinking about this because in May it will be ten years since Eric died, and right now it’s ten years since Eric began to be really sick, though we didn’t realize yet that he was dying.

Dawn has crept further and further into the night and now I’m waking up many mornings with light already in the sky, after months of being up for hours in the dark. Birdsong comes along with the light, the beginning chatter of birds awakening to the next season, starting to build nests and call to each other to mate and start the whole cycle of birth and death again. The rise in morning birdsong is burned into my psyche as signifying the rise in Eric’s cancer. Birdsong = Impending Death.

Not very spring-like. But there it is, the twittering of purple finches and melodic call of a robin and the chink of red-winged blackbirds. I wrote a poem about it this morning, one of many in a long line of poems about what spring birdsong means to me now (like the first poem in The Truth About Death, which I posted here around this time last year).

But there’s a twist this year. I also made a collage. Does that have anything to do with the tenth anniversary of Eric’s illness and death? Or is it simply the process of aging and getting better at giving myself permission to do things because I want to, because I have an urge to create in a different way, because I care less and less what it means and just want to do it.

I’m signing up for a drawing class. Maybe next I’ll draw the birds.

What I Kept

I love standing at my new desk, stroking a brush with long dark bristles across a collage of dried leaves, spreading acrylic varnish that’s both protective and adhesive. The motion is methodic and fluid, comforting. I’m making something, a physical object, following a non-speaking muse when choosing the placement of the leaves and ferns, the colors, moving shapes around until it looks right.

I’ve gone through many of the piles of paper and old magazines and cards in my study this week, organizing them by type, maybe some day by color or theme. For now the old DoubleTake magazines (who remembers that incredible journal from the late 90’s and early 00’s of top-tier writing and photography, and what a blessing I kept them and then David wanted them in his studio and now they’re back with me), Lapham’s Quarterly (outstanding illustrations and graphics) and art advertising books from Santa Fe and the coast of Maine, are together on a shelf, along with other random magazines. Postcards are sorted in cubby holes of a shelving unit I built in an adult education woodworking class 25 years ago, both new cards and antiques, including souvenir folders of cards from the 40’s, sets Eric’s father was mailing home when he was in the army during WWII. Eric collected the antique Squam postcards. I have decades of Mother’s Day and birthday cards from Adrienne and Sam. Those I’m saving to save, not to collage.

“Where did these come from?” David asked when I made my first collage with the dried leaves earlier this week. Our trip to Rockport, Maine in the fall of 2008, when we were only months in love and reeling from the death of David’s wife two months before, a quick cancer death like Eric’s. David and his wife were in the midst of a divorce when he and I met, but once she was sick he disappeared from my life to go back home and help. It had been a hard summer, a terrible time for David’s family. By the fall his back had given out and he could hardly walk. That he and I were away together, alone, with trees full of red leaves in every imaginable shape of maple, had seemed miraculous. I walked around the neighborhood where we were staying, carefully picked leaves and folded them in paper towels. I needed to hold on to something beautiful. Tucked in books I had with me, I brought the leaves home and somehow kept track of the pile of preserved fall and then there they were, in my study.

Or, my studio. It’s been a very satisfying week.

Another Week

Another week, another seven small poem collages. I’ve managed to fit in enough textual/visual — visual/text art work in the last week to have created something every day.

The interplay of what happens between the poem I write and the collage I make, editing the poem, moving images around the page, adding and subtracting shapes and colors, faces and symbols, getting the poem on the page, is shaped in part by a right brain that doesn’t always get to talk when I’m straight ahead writing.

David and I are in Brooklyn for a long weekend, spending time with the grandkids and some time in the city. Yesterday we had breakfast in a cafe around the corner from the BedStuy Brownstone where we’re staying, and I was finishing the drawing and writing on the collage I’d started the day before.

“Is she an artist,” the waitress asked David. Ah. Yes. Just like a writer is someone who writes, an artist is someone who makes art.

1.11.16

wind breaks against the front of the house

where we sleep

I wake

to the growl and whistle slapped back

a path

1.13.16

Yesterday:

Big white in flight

stops in a tall pine

at the edge of a graveyard

bald vision

bald view

still white.

Today:

White overnight enough

to hold dawn’s peach.

1.15.16

Ball

Orange & black

soccer

arcs from high

above the road

bounces at the front

of the car.

Quick check

for the child. No, only

a wall that contains

the game

unseen, unheard, unhidden.

A Week Of Doing It

Text with images has been brewing in my creative imagination for a long time. I want to make visual art, I’ve wanted to for years, and having worked with words for so long any visual art that incorporates words attracts me. Maybe I could do that. Touring museums I’m drawn to paintings and collages that incorporate text. Graffiti tags intrigue me, with their interlocking and mostly indecipherable letters, an alphabet more visual than textual, a signature that’s image.

It’s not that I’ve never worked on a visual level. When I was much younger I did small watercolor paintings copied from children’s books but haven’t painted since. I’ve cross-stitched samplers that I designed myself, transformed a denim skirt into a tapestry of crewel work, and knit countless sweaters, hats and mittens, creating designs with different color yarns as I go. When Emilio was younger and obsessed with animals I drew horses and cows for him, which I was able to do by carefully looking at the plastic animals he played with. If I’m at a meeting without knitting my doodling fills whatever margins are available.

But moving in to intentional visual art work as a legitimate use of my creative energy has been hard. Who am I to paint or draw or make collages? A question that makes no sense, because who am I to write poems or a memoir or a novel? Does having been published make writing more legitimate? What about all the writing I do in my journal, the novel I wrote and have never looked at since, the boxes and boxes of writing stored in my barn and my new file drawers that I’ve never tried to get published, much of it never taken past a quick first draft?

So I’m pushing the questions aside and finally giving myself permission to be visual. The transformation of my study to incorporate an art desk is well underway, and I’m not waiting for that to be done to get working.

I’ve been faithfully Grinding for over a week and each day I’ve made a collage to hold the words I’ve written. In fact, for the last two days the image has come first because I’ve been writing erasure poems, a process of crossing out words on a page of text and making a poem from what’s left. The erasure itself is part of the image.

How absorbing this is! Absorbing enough I’m not worrying about what it’s for, who am I to do it, what it means, what it is. I’m just doing it.

Day Two — Seaside and Sky

Steely water runs out of a creek, cutting a bank through sand before disappearing into the froth and fury of the ocean, blue beaten white as it crashes on the beach. The wind is hard and cold, clouds low. David and I walk with our heads down, trying to keep the chill off our faces.

We gather driftwood sticks, feathers, black curled strings and bubbles of dried seaweed. I’m imagining a mobile of sailboats hung from sea bleached wood, feathers floating between the curls of seaweed. There are small white feathers, long broad gray ones, one with white circles on a dark background. The mobile will be for my father, a man who grew up on the ocean, who taught me to sail, who took me and my sisters to the beach during hurricanes so we could watch the surf smash over the seawall. I’m making an ocean he can hang in the house, a beach above the table where he paints sailboats and marshes and waves.

We guess the distance from one end of the beach to the other. We get it right. When we turn to walk back the clouds open for a few minutes of sun and the warmth is startling, backs to the wind, faces to the light. The far shore is luminous under a sky the color of a new bruise, blue beginning to bleed into black. No yellow yet.

By the time we’re headed home it’s so dark I feel lost. I can hardly see the road, the early night so heavy we’re wrapped in blankness. The tunnel of winter is coming, an approach I feel more than see.

My father is 91, he hasn’t been on the ocean for over a decade. He never walks the beach anymore, though he sits by the harbor and watches boats come and go. He takes photographs and paints, creating a seaside. I’m creating the sky.

Another Day Then Again

In December 2012 I began writing two weeks before the winter solstice and wrote at least 300 words every day — Two Weeks to the Turn, I called it. It was a way to get myself writing every day, and a way to deal with the darkness. I’ve done it every year since and am about to start again.

This year the solstice is on December 21 at 9:49 p.m. EST in New Hampshire, so beginning on Tuesday I’ll write every day for two weeks. Maybe I’ll bump right up against the moment of the turn, pen in hand or fingers on the keyboard. The approaching solstice is a boundary to wrap my intention around. The fact of its own repetition inspires mine.

My father has been taking a photograph of the marshes near where he and my mother live every month for two years now. He’s arranged his favorite photograph from each month of 2014 on a big board, the months labeled on white slips of paper. It’s a terrific piece of art, the whole of the project greater than the sum of each image.

What is it that’s so satisfying about an organizing principle for creativity? I think artists, like me, who struggle to stay in a focused daily practice gravitate towards work that’s gotten done because someone made a commitment to practice creativity every day.

William Stafford got up early every morning for decades and wrote a poem. He wrote that in those early hours “something is offering you a guidance available only to those undistracted by anything else.” In his commitment to the practice, Stafford was “training himself to hear and feel his way back in touch with distant places, ages, epochs,” wrote critic Laurence Lieberman. To get to the deeper level of any art requires training and training requires repetition. It’s how you get better at doing anything.

So I love my father’s photographs and how he’s displayed them. I love that I have two friends who I email every Monday with a writing prompt, and another friend I trade writing with on Mondays, not to be critiqued, but to be accountable to someone to meet a stated goal, 2,000 words a week, or completion of self assigned writing tasks. Practice.

Starting Tuesday, I’ll write at least 300 words every day for two weeks. When I did this two years ago much of it ended up on this blog, my writing organized around an idea from another writer friend who asked me, “With all the sadness that’s underlined your relationship since you met, how do you and David move towards happiness?”

I don’t have an organizing question this year, but I have commitment. I’ve been slacking off on the practice lately and need to get back to it. You’ll be seeing the result here.

Sadness Moving — Reflections

When I write about grief and sadness my blog gets a lot of hits. Same when I write about my travels. What’s the connection? What if I wrote about both at once?

Thursday I went to Boston to the Museum of Fine Arts, meeting up with my youngest sister Meg and her husband John and Chris’s Jon. Family disappears so I’m hanging on.

Wednesday night I went to Portland to hear Ry Cooder and Ricky Skaggs play such accomplished music, accompanied on piano by Buck White (85 years old!) and his daughters singing exquisite harmony, I remembered how to be happy.

I’m hunting art. Moving. Years ago a friend from my work life spent a weekend here. She came to NH to do a half marthon with me so I would think she’d have known what she was in for. But a day in to our visit, before all our mutual friends showed up as running support and talking-drinking-eating buddies, she watched me move around the kitchen as she sat at the table.

“You really can’t sit still can you?”

“Nope.”

For years she made a joke of the fact that 4 miles into the half marathon I abandoned her and moved off ahead. I couldn’t run that slowly. It hurt.

If I could slow down I would.

If all my reflections on life created an infinite pattern, I doubt it would be as beautiful as “Endlessly Repeating Twentieth-Century Modernism” by Joshiah McElheny. His piece at the MFA is stunning and brilliant, a perfect, mirrored box of glass objects that reflect into an unending distance as each object holds its own jeweled reflections.

Now I’m wearing some of Chris’s jewelry along with her shoes and socks and jacket and jeans.

I’m not planning to go anywhere for a while.

We’ll see how long that lasts.