A steady clack comes out of the bedroom where the plastic pull knob on the cord for the blinds taps the sill, pulsing in the wind through the window opened to get air into the house.

Sunshine glints off the screens in the four large windows in my study, screens that will come out in the next few weeks.

There was a frost while we were away, nasturtiums drooping on themselves, the basil brown and wilted. Was it last night?

Cows still graze the pasture across the street, framed by a branch of the old maple sprouting yellow, orange and red.

When I got home this morning I opened my journal to write about our last few days — all the places and family we’ve visited, the historic First Parish in Concord (this is the congregation Emerson and the Alcotts were part of, where Thoreau’s memorial was held) to meet with the minister who’ll be involved in the memorial service for Chris, the astonishing America Is Hard To Find exhibit at the equally astonishing new building now housing the Whitney Museum, watching Ava clap her gold moccasins together and laugh, fitting the pieces of a table-top-size Spiderman together with Emilio, last night in a Rodeway Inn off the traffic circle in Greenfield, MA, a former Howard Johnson’s with a glass shelf of spectacular crystal rocks behind the check-in desk that the clerk said no one knows the history of, this morning’s drive in pre-dawn darkness into the hills to the west and then east again into autumn smoke rising from rivers and dew — and instead I drew a map, with the buildings and skylines and houses we’ve visited, lines with arrows tracing our route, and then connecting the words when I began to write with language.

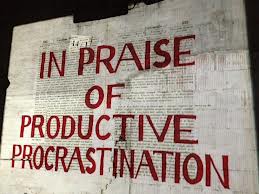

Is art hard to find or hard to find the time for?

For the first time since the beginning of July, I’m home with no immediate plans to be anywhere else overnight. What will I find the time for?

* From Whitney exhibit description of the painting above: This monumental painting offered Krasner an outlet during a time of deep personal sorrow. The year before, her husband, fellow artist Jackson Pollock, had died in a car accident. In the wake of this sudden loss, Krasner remarked about The Seasons, “the question came up whether one would continue painting at all, and I guess this was my answer.”